Introduction

As a junior doctor in the NHS, entering the ward for the first time can be overwhelming. Everyone except you seems to understand the unspoken rhythm, the fast-paced conversations, and the strange terminology.

This article aims to be your survival guide – and more than that, a growth map. As a Clinical Teaching Fellow, I’ve mentored many FY1s and international medical graduates (IMGs), and the one thing they all share is that sense of nervous anticipation.

Mastering the ward round isn’t about getting everything perfect. It’s about being prepared, communicating clearly, and recognising when to ask for help.

- Why Ward Rounds Matter

- Preparation Before the Round

- Template for Ward Round Notes

- Presenting Patients: Tips & Examples

- What is a Confusion Screen – and When to Request It

- When to Escalate to Seniors: Common Red Flags to Spot

- Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Working with the Team

- Jobs and Documentation After Ward Round

- Teaching and Learning on the Ward Round

- Managing Complex or Deteriorating Patients

- How to Handle Being Put on the Spot

- Some Sample Statements You Can Use

- Closing Advice

Why Ward Rounds Matter

The foundation of inpatient medical care is ward rounds. Clinical decisions are reviewed, updated, and communicated primarily through them.

Ward rounds are an excellent opportunity to learn, in addition to providing patient care. Every round offers a chance to learn and develop, from going over medication and pathology charts to observing your seniors use clinical reasoning in real time.

The ward round has a direct effect on MDT coordination, escalation decisions, discharge planning, and patient care.

Preparation Before the Round

Preparation is your key to feeling confident and in control when the consultant looks at you and says, ‘Tell me about this patient.’ Here is a basic structure you can follow:

Here is a basic structure you can follow:

- Start by reading the patient list early – even 10 minutes makes a difference.

- Write down what happened overnight: Has the patient had a fever? Are you confused? Did anyone fall?

- Look at the most recent observations: NEWS2, oxygen use, and blood pressure trends.

- Look over the blood tests and pictures. If you don’t know what something means, write it down and ask.

- Look at the drug chart: Are there any new antibiotics? Did you forget to start or change a medication?

- Be aware of their care limits and any decisions still to be made (TEP forms- Treatment Escalation Plan), DNACPR or moving to HDU.

Template for Ward Round Notes

I will start by giving a basic layout we commonly encounter in the NHS:

55YO male admitted on 01/01/2025

PC: Cough, SOB, Chest pain

PMHx: HTN, T2DM, AF

SHx: lives alone in a house, no carers, ex-smoker, does not drink alcohol, mobilises with a frame

DNAR in place, AMT=10/10

Issues:

1. LRTI

Many juniors find it helpful to follow a repeatable format during each patient review:

- Patient ID and Bed Number- These are usually printed and are pre-filled in the ward proforma

- Reason for Admission and issues

- Latest Observations and NEWS2 Score

- New Symptoms or Concerns

- Blood Results and Imaging

- PMHx and Medications

- Day Tasks (such as referrals, discharges, TEP and DNAR form)

Presenting Patients: Tips & Examples

It is essential to highlight the presenting complaints. We learn to present in structured formats such as SOCRATES and ODIPARA in medical schools. However, things are different in ward settings, and a concise and clear narration is elemental.

Don’t worry; these skills come with experience and practice. You will learn them best when you join MDTs and start playing as a team member. A good clinical practice guide is also available on the GMC for standard rules.

Basic Structure You Can Use:

- Name, age, diagnosis

- What’s changed since yesterday?

- Relevant obs, bloods, imaging

- Your summary and plan suggestion

Example:

“Ms James is a 69-year-old with COPD exacerbation. Day 3 of IV antibiotics. Now afebrile, saturating 95% on air. CRP down from 112 to 48. No new concerns. Plan: Consider switching to oral and physio input for mobility and aim for discharge tomorrow.”

What is a Confusion Screen – and When to Request It

An elderly patient who has recently developed confusion is a common situation you will come across. Infections, metabolic disorders, or adverse drug reactions are among the causes.

A confusion screen typically includes routine medical bloods as well as LFT, TFTs, Vitamin B12 and folate, glucose levels and investigations such as chest x-ray or urine mc&s. Ordering a confusion screen can help uncover treatable causes of delirium.

When to Escalate to Seniors: Common Red Flags to Spot

You need to understand the limitations and responsibilities of being a junior doctor. For the safety of your patients, you need to learn when to escalate. The following are some typical warning indicators that should be addressed immediately and brought to the attention of seniors:

- NEWS score of 5 or more

- Uncorrected hypotension or worsening oxygen demand

- New chest pain, ECG changes, drop in GCS, or new confusion

- Changes to UnEs such as AKI or drop in haemoglobin or melena

Even when you are in doubt, it is a good idea to seek support from seniors. Reluctance and fear of getting embarrassed are not uncommon, but believe me, no one will ever criticise you for flagging early.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

1. Guessing blood results

Always check the values before presenting. Minor errors are acceptable, such as CRP of 60 vs actual CRP of 66. Significant errors, such as a CRP of 600, are a disaster.

2. Forgetting to check the drug chart

Identifying medications that were suspended, discontinued, or newly started, along with the reasons for these actions, helps in answering questions and explaining reasons clearly.

3. Not writing down the plan

A clear plan often starts with bullet points or numbering. Highlight the important ones early and create check boxes for the ones you need to follow up on. Try writing clearly; otherwise, you will find yourself with a nurse who’s irritated and has to clarify what’s written in your notes.

4. Being afraid to ask questions

Remember, it’s okay to ask questions. It’s encouraged. If you can’t hear the consultant or miss something, politely ask for clarification. Consultants would rather you ask than make unsafe decisions.

Working with the Team

You will often find yourself sitting in early board rounds or MDTs. Usually, an introduction is not necessary, but make sure you are heard if they don’t know who you are.

Wise consultants often say, “Nurses are the first to spot patient deterioration, make them your friend and you will live happily ever after”.

Early morning rounds will sometimes include the sister-in-charge mentioning key concerns before starting the list.

As the number goes on, they will mention the concerns which you pick and jot down in your notes. These can include things such as new diarrhoea, new confusion, antibiotics missed, patient declined medications, safety concerns, etc. Make sure you have a good rapport with them.

Ask questions right away if you don’t understand an instruction. Errors and delays result from guesswork. Mention any tasks that are delayed or need assistance, and the team can always help you out. Everybody has been there.

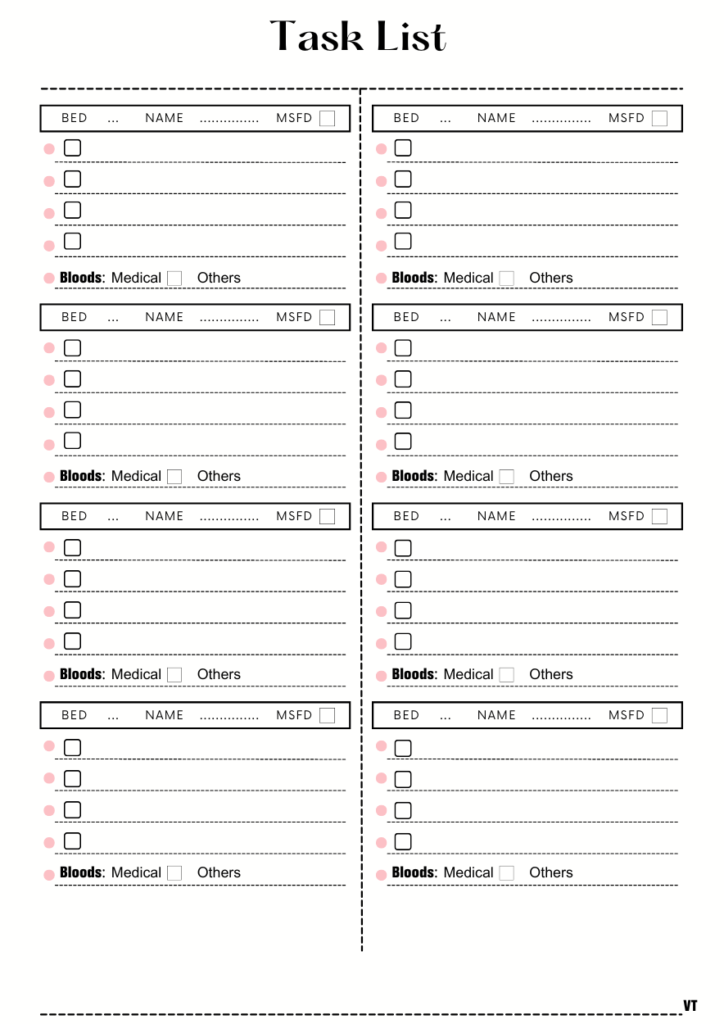

Jobs and Documentation After Ward Round

Most junior doctors habitually make a one-page task list with boxes as tick marks to track down everything. You will learn it too.

If you want a downloadable version, I will attach one below:

Here are some common points to keep in mind:

- Utilise a job list that is shared with the SHO or another FY1 member. Assign work effectively.

- Make urgent tasks, such as blood draws, scans, medication changes, and discharges, a priority.

- Write down the plan in concise, well-organised notes. If appropriate, use SBAR.

- Verify that referrals have been received and that results are constantly pursued.

- Communication prevents instructions from being missed, so don’t leave the ward without giving the nurse an update.

Teaching and Learning on the Ward Round

Ward rounds aren’t just for clinical decisions; they’re teaching opportunities in disguise. As a junior doctor, try to engage with your consultants and ask questions for new learning opportunities.

- Please pay attention to how consultants arrive at their diagnoses.

- Examine the decision-making process used by them.

- Ask questions when it’s appropriate, particularly at the end of the round or during rounds.

If you don’t understand a term or decision, jot it down and ask your registrar or SHO later. This turns every round into a valuable learning experience.

A good example of initiating a conversation with your consultant would be to ask why we are giving furosemide to a patient with impaired kidney function in a heart failure patient. Cardiorenal syndrome is an area I’m still learning, but consultants are very experienced and can help you learn things that go way beyond your textbook learning.

Managing Complex or Deteriorating Patients

Not every ward round is simple. Some patients have complicated medical conditions, are unstable, or are in distress. Although these can be daunting, they are manageable if you have the correct attitude.

For deteriorating patients, focus on:

– Current NEWS2 score and trends

– Oxygen needs and escalation plan

– Relevant bloods: lactate, creatinine, Hb

– Senior input – escalate early

If necessary, divide a complex patient into their organ systems, such as the respiratory, cardiovascular, renal, etc. Pay attention to the changes that have occurred since the last review and the direction that things are taking.

Utilise organised, structured documentation that effectively summarises complexity while outlining a clear strategy. The team benefits from your clarity.

How to Handle Being Put on the Spot

Another common situation is finding yourself in an awkward spot where you have no answer. Some tips that can help you confidently tackle the difficult situation are:

- Be honest and say- ‘I’m not sure, but I can check now.’

- Guess only if you feel safe to do so.

- Exhibit that you are happy to find out the answer, such as ‘I don’t know the answer yet, but I can check quickly if you allow’

I understand that many people expect doctors to be all-knowing, but no good senior will expect junior doctors to be that way. What matters are attitude, clarity, and patient safety.

Some Sample Statements You Can Use

Here are some phrases to keep in your back pocket:

– ‘I’ve reviewed the patient. Vitals are stable, and there are no new concerns from nursing staff.’

– This is day 3 of IV antibiotics, CRP is trending down, and the patient is clinically improving. Shall we switch to oral?’

– ‘There’s a new drop in GCS, and I’ve requested a CT head and initiated a confusion screen.’

Closing Advice

The first few weeks of ward rounds may feel chaotic – that’s normal. Learning the flow, expectations, and medical judgment requires time.

Every ward round is a chance to learn. Please don’t rush through it. Watch how your registrar assesses patients. Listen to how consultants explain things. Ask questions: they’re expected.

Being a junior doctor isn’t about perfection. It’s about safety, consistency, and growth. With time, the chaos will make sense.

You are allowed to feel overwhelmed. You’re also allowed to be proud of yourself for showing up, asking, and improving day by day.

Be kind to yourself. Keep preparing. Ask questions. And most importantly, remember that every senior around you was once in your shoes.

You’ve got this! And if ever in doubt, start with what you do know. The rest will follow.

You belong here, and you are doing better than you think.